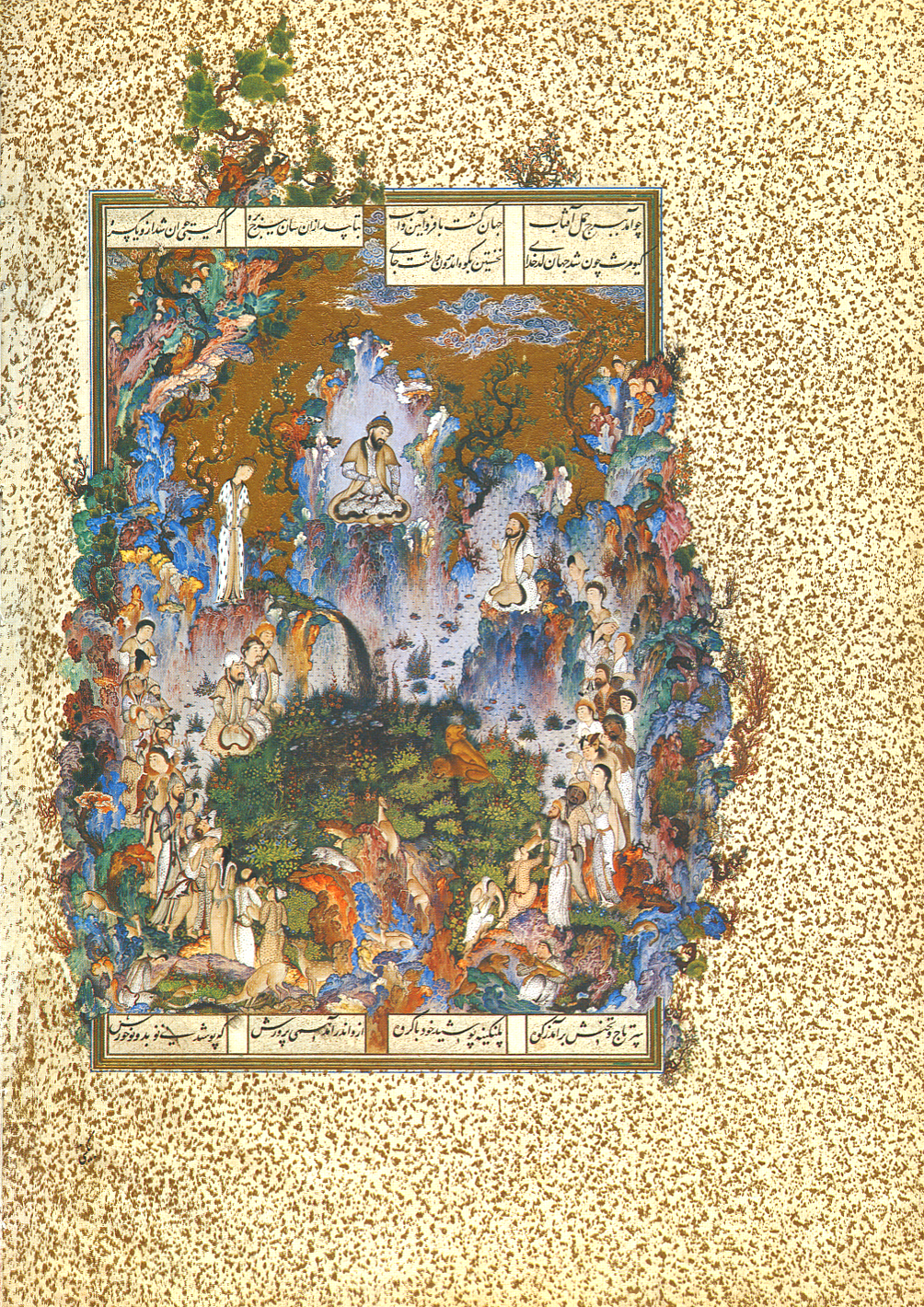

نقاشی سوم را از میان ۲۵۸ برگ مصور شاهنامهی طهماسبی انتخاب کردهام. این برگ که نقاشش سلطان محمد تبریزیست، فقط حاصل تلاش یک نقاش نابغه نبوده، بلکه حاصل تلاش هنرمندان زیادی بوده که در کارگاه سلطنتی صفوی زیر نظر او کار میکردند. نگاه کردن به این شاهکار تصویری صفویه مرا ناراحت میکند؛ چون به یاد سرنوشت غمانگیز این کتاب مصور میافتم که به دست دلال اروپایی تکه تکه شد و هر قسمتی از آن در جایی از دنیا میان کلکسیونهای مختلف است. کتابی که درک عظمت آن مستلزم یکجا بودن آن است. و این برگ که «بارگاه کیومرث» نام دارد در مجموعهی موزهی آقاخان نگهداری میشود و مثل اکثر نقاشیهای این لیست، با وجود اینکه این نقاشی در کشور خودم و توسط نقاشی ایرانی آفریده شده، از دیدن بیواسطهی آن محرومم.

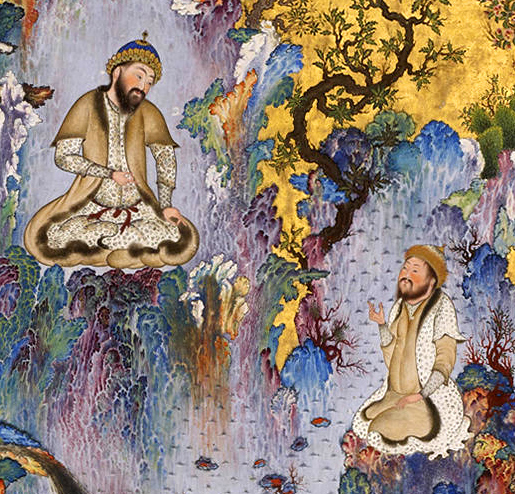

این نقاشی با وجود اینکه ذائقهی بصریمان به الگوهای زیباییشناختی غربی عادت کرده، کماکان شگفتانگیز، و هزاران برابر رازآلود است. به نظر من این اثر قبل از هر چیز، یک نقاشی منظره است. منظرهای که در آن اتفاقی مهم جریان دارد، ولی تمام عناصر انسانی آن حتی کیومرث، فرزندش سیامک و نوهاش هوشنگ که بهعنوان گل تصویر در مرکز قرار گرفتهاند جزئی از این منظرهی طبیعی هستند و این از جهانبینی نگارگران ایرانی میآید که انسان را جزئی از کل طبیعت میدیدند. سلطان محمد دلیلی روشن برای اینکار داشته. شعر انتخابی از بخش اول ابتدای شاهنامه در بالای صفحه اینطور شروع میشود:

چو آمد ببرج حمل آفتاب / جهان گشت با فر و آیین و آب

بتابید ازان سان ببرج بره / که گیتی جوان شد ازو یکسره

کیومرث چون شد جهان کدخدای / نخستین بکوه اندرون داشت جا

که تاکید بر فصل بهار و منظرهی کوهستانی دارد. فصل بهاری که با شکوفهها و رنگهای تند و تیز آبی، بنفش، سبز، سرخ، طلایی و نقرهای بدان اشاره میشود.

کیومرث، نخستین پادشاه شاهنامه، تاجگذاری خود را در کوهستان با فرزند و نوهاش و مردم و موجودات دیگر، از حیوانات گرفته تا گیاهان، جشن میگیرد. سلطان محمد میلیمتری از این کادر را از جزییات خالی نگذاشته است، همانطور که میلیمتری از طبیعت از جزئیات خالی نیست. همهجای تصویر اتفاقی در حال رخ دادن است. اگر این نقاشی را با یک پروژکتور روی دیوار بیاندازید و آن را در سایز دو متر در یک متر ببینید، باز هم از جزییات زیادش شگفتزده میشوید. حالا فرض کنید به همین تصویر در ابعاد تقریبن A4 نگاه کنید. فوران اطلاعات بصری هیجان وصفناپذیری را در شما بوجود میآورد.

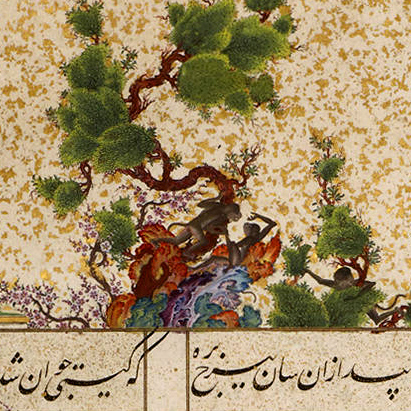

رنگها بدون اینکه کلیت تصویر را متشنج کنند، شجاعانه، خالصانه و دستودل بازانه بهکار رفتهاند. بیدلیل نیست که نقاشانی مثل ماتیس از دیدن چنین آثاری به وجد میآمدند و دوست داشتند رنگهای خالص را با جسارت بیشتری بهکار ببرند. کاش رنگ نقرهای که در مرکز تصویر برای نشان دادن آبشار و دریاچه بهکار رفته بوده و بعدها به دلیل فعل و انفعالات شیمایی به رنگی تیره تغییر یافته، هنوز به شکل اول بود و میشد حالت اصلی تصویر که هنرمند قصد آن را داشته دید؛ ولی با وجود چنین تغییر بزرگی در رنگ، هیچ خدشهای به انسجام رنگی اثر وارد نشده چون هنرمند به هیچ عنصری از تصویر اجازه نداده آنقدر تاثیرگذار باشد که حذف شدن آن کل تصویر را تحت الشعاع قرار دهد.

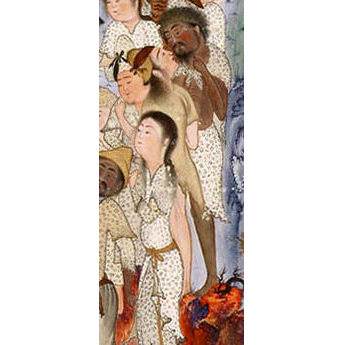

نبودن سایه، زمان خاصی از روز را پیشنهاد نمیکند ولی بهخاطر آسمان طلایی دوست دارم تصور کنم دم غروب است. مردم، سیاه و سفید و حیوانات از شیر تا آهو، در صلح و آرامش دور هم جمع شدهاند. هیچ خبری از سلاح یا جنگ نیست و همه خوشحالاند و از بودنشان لذت میبرند. خوشحالی را حتی در چهرهی صخرهها هم میتوان دید. بله. صخرهها هم، در اوج ظرافت، در این تصویر چهره و بیان فردی دارند و نسبت به اتفاق بزرگی که رخ داده واکنش نشان میدهند.

تصویر بیشک مملو از جشن و شادی است؛ اما نقطهی عطفی که آن را تبدیل به شاهکاری بیبدیل میکند، نگاه غمانگیز و پرحسرت کیومرث به پسرش سیامک است که سلطان محمد با نبوغ و زیرکی تمام در لایهای عمیق از تصویر گنجانده. در ۵ بیتی که در بالا و پایین تصویر به خط نستعلیق نوشته شده اشارهای به این موضوع نشده؛ ولی سیامک قرار است با سپاهش به جنگ برود و روز بعد کشته شود. کیومرث این را میداند و از این اتفاق سخت اندوهگین است.

نقاشی ایرانی را کسی با بیانگری چهرهی پرسوناژهایش نمیشناسد. چهرهها از الگویی فرادست گرفته میشوند که نژاد خاصی را نمایندگی میکند و علیرغم تفاوتهای جزیی صورتها، در اکثر مجلسهای نگارگری ایرانی نمیتوان از طریق چهره به حالت روحی درونی شخصیتها رسید. ولی سلطان محمد، با تمام محدودیتهایی که سنت چهرهنگاری بر او اعمال کرده، در نهایت استادی حسرت را در نگاه کیومرث گنجانده است. انقدر هنرمندانه که اگر بیننده به نقاشی با دل و جان نگاه کند میتواند بغض کیومرث را در گلوی خودش احساس کند.

این نقاشی را میتوان ساعتها نگاه کرد و چیزهای جدید از آن یاد گرفت. میتوان در موردش ساعتها حرف زد و هنوز هم تفسیرهای بیشتری از آن پیدا کرد. میتوان به تک تک پرسوناژها و موجودات روینده و جهندهی آن فکر کرد. به میمونهای بازیگوشی که بیتوجه به کادر زخیم و طلایی از آن خارج شدهاند و نوک درختی با هم بازی میکنند. به مردی که پایین تصویر بچه شیری را بغل کرده و با شیر دیگری بازی میکنند یا مرد سیاه و زن سفیدی که گویی دارند همدیگر را میبوسند و در گوش هم عاشقانه صحبت میکنند. دنیایی که کیومرث بر آن فرمانروایی میکرده، از نگاه سلطان محمد، دنیایی بوده جذابتر از بهشت جاودان: زیبا و زنده و نو؛ و در عین حال اندوهگین و فانی.

I chose the third painting from 258 illuminated pages of Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp. Although This folio is a work by Soltan Muhammad Tabrizi, it’s the result of a team work by a group of artists who worked under his supervision. Looking at this masterpiece of Safavid era makes me sad, because it reminds me of its heartbreaking fate to be torn apart by an European art dealer and being spread around the world in different collections. Understanding the grandeur of this Shahnameh is only possible when it’s gathered as a single book. And this folio, which is called “The court of Kayumars”, is held in Aga Khan Museum and that means like many other paintings in this list, I’m deprived of the chance to look at it directly, and not through internet and image files, despite the fact that it’s a work by an Iranian painter. For me, it’s a stolen treasure.

Although our visual taste is accustomed to Western aesthetics, this Middle-eastern masterpiece looks as magnificent, appealing and extremely mysterious. In my eyes, this piece is first of all a landscape. A landscape with an important happening, but the human elements are a part of nature and this is of Iranian painter’s worldview that sees human as a natural phenomenon. Sultan Mohammad has a good reason to make landscape the first priority of this image. The selected poem which the picture is representing says:

This order, Grace, and lustre came to earth

When Sol was dominant in Aries

And shone so brightly that the world grew young.

Its lord was Kayumars, who dwelt at first

Upon a mountain; thence his throne and fortune

Which emphasizes on spring and mountain scenery. A spring with blossoms and sharp bright colors of blue, violet, green, red, gold and silver.

Kayumars is the first king of Shahnameh who is celebrating his coronation upon a mountain with his son and grandson and people and other creatures from animals to plants. Sultan Mohammad hasn’t left a single millimeter of the picture without detailing, like nature where there isn’t a bit without detail. There is something going on everywhere in this landscape. If you use a data projector to project the painting on a wall, you will be surprised by all the details. Now imagine looking at it in the size of an A4 paper. The blast of visual information results in indescribable excitement.

Color is used with courage, purity and generosity without cluttering the whole image. It’s no surprise that Modern painters like Matisse were excited to see such miniatures and wanted to use pure colors as daring as them. I wish the silver color, which is now converted to a dark tone of green because of chemical interactions, would be the way artist intended so I could see the painting as it used to look like; but despite this important change, the coherence of the picture still remains, because the artist doesn’t give exorbitant importance to any part of the picture.

The absence of shadow doesn’t suggest any particular time of the day, but I like to imagine that it’s almost sunset, because of the golden sky. People, black and white and animals, from lion to dear are gathered peacefully. There isn’t any signs of war nor any weapons and everybody is happy and enjoying theirselves. You can see happiness even in the face of rocks, which are elegantly with faces and expressions, reacting to the happening.

The picture is full of joy and celebration; but there is a turning point which makes it a masterpiece: The sad look of Kayumars at his son, Siamak, which Sultan Mohammad has subtly put on his face. This is not in the 5 verses of the poem that are mentioned in the picture, but later on Siamak is going to go to a war and he is going to die and Kayumars knows this and is suffering from the fate of his beloved son.

Iranian miniature is not famous for the expression of the faces of its figures. Faces are derived from a defined pattern that represents a particular race, and it’s not possible to get into a person’s feeling in a miniature through the expression of their face. Despite all of these limitations of the Iranian miniature tradition, Sultan Mohammad has shrewdly put an expression of regret on Kayumars’ face. So effectively that if the beholder looks heartily at the painting, they can feel the grief and regret in their own heart.

You can look at this painting for hours and learn new things from it again and again. You can talk about it and find new interpretations every time. You can look at the figures and creatures and think about their being. Three playful monkeys who are careless to the golden borders of the picture and playing with each other on the top of a tree. A man at the bottom who is hugging a lion and playing with another one. Or a black man and a white woman who are kissing and flirting at the right side of the picture. The world ruled by Kayumars, in the eyes of Sultan Mohammad, is more interesting than the eternal paradise: It’s beautiful, alive and new; and at the same time lugubrious and immortal.