Amin(Ameen) MoAzami/ 1993, Gonbad-e Kavous, Iran

Based in Tehran, Iran

This collection of nineteen etchings presents a layered story of Tehran. Moving between historical references and contemporary life, the prints portray how the city’s underlying forces interact through architecture, streets, people, and their icons. Together, they offer a cross-section of Tehran’s urban experience, from monuments to everyday objects, from planned structures to improvised acts.

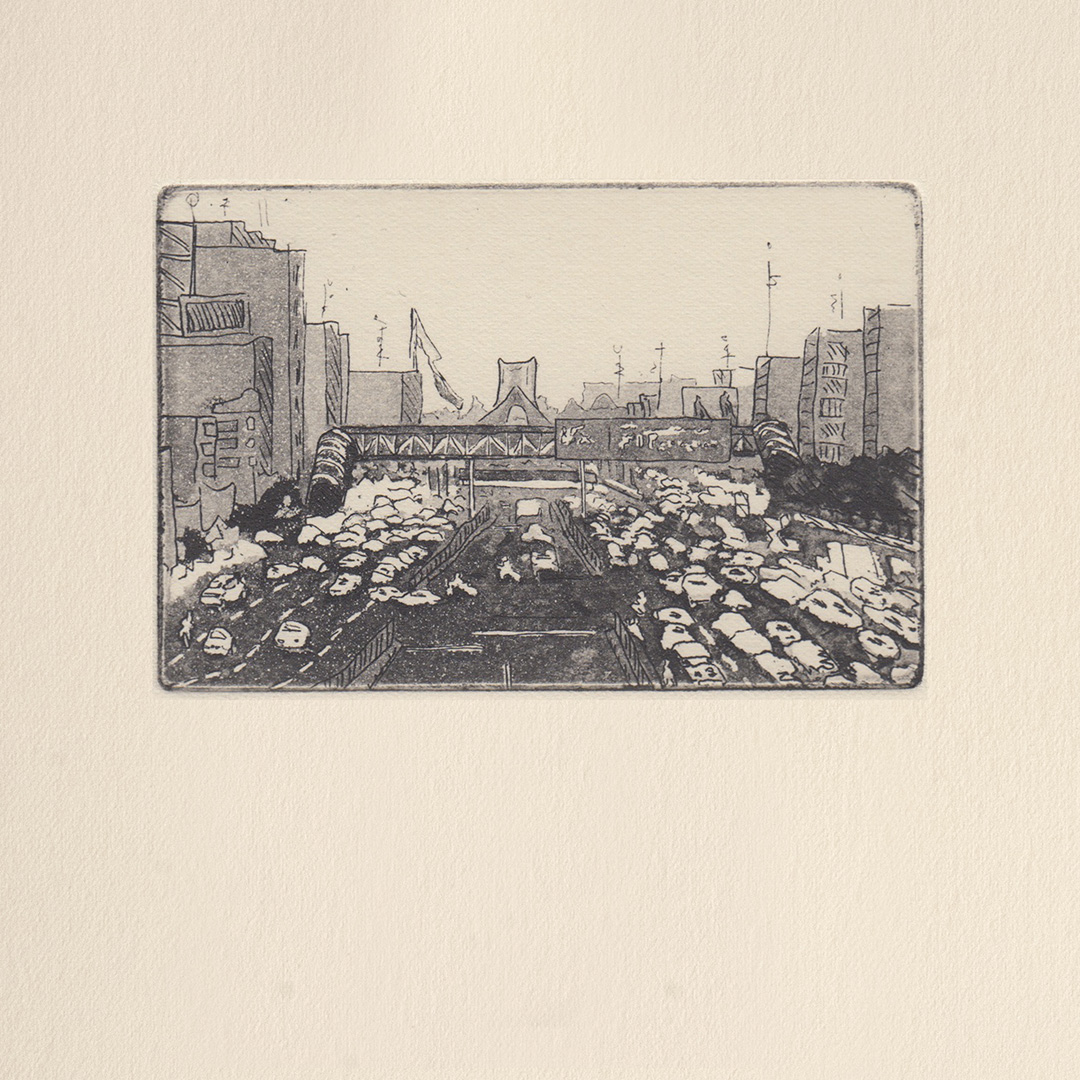

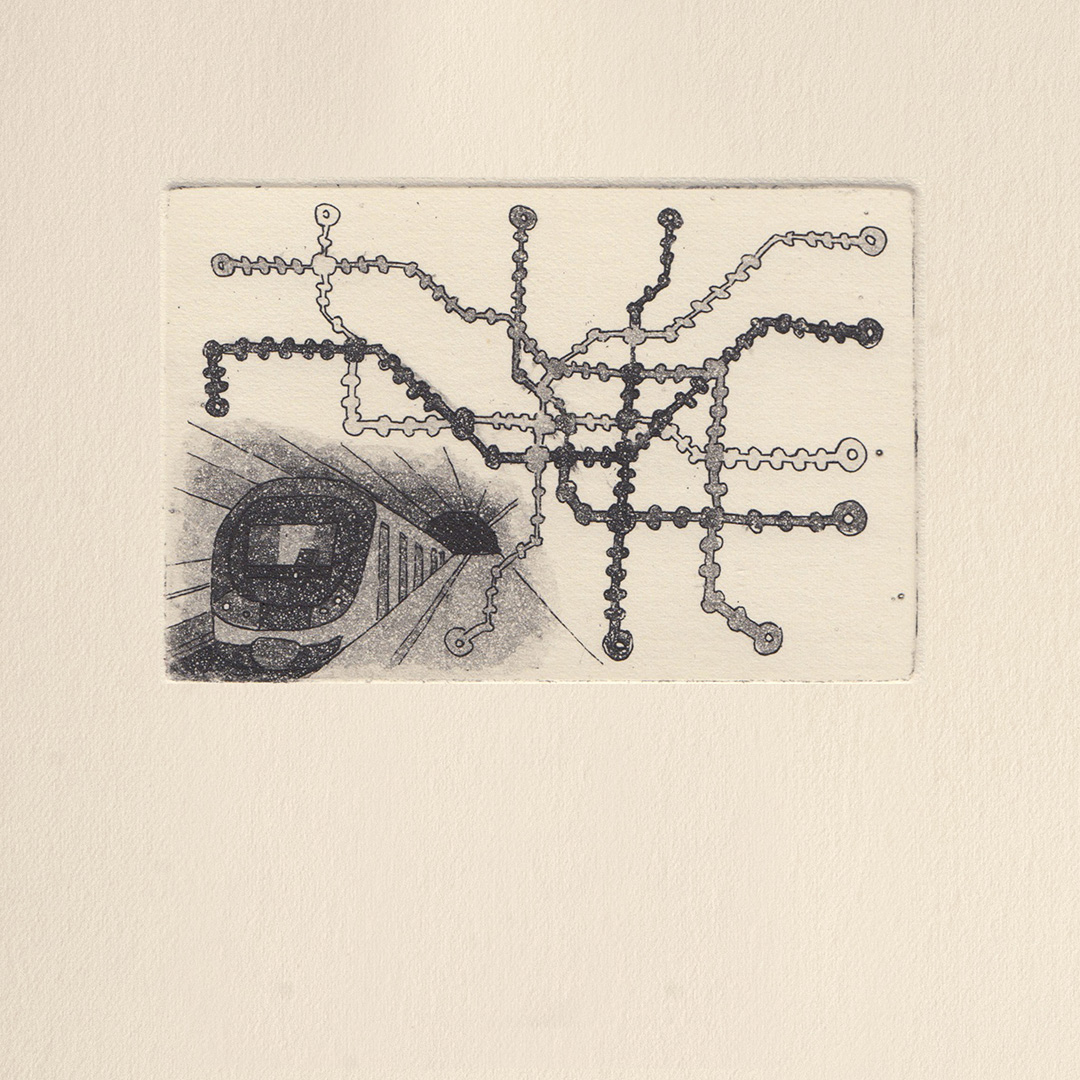

The Azadi Tower (Print 1), the most iconic symbol of Tehran and once a national emblem of modernity, appears amidst a tangle of traffic and chaos. Around it, infrastructures like an overhead pedestrian bridge and metal fences suggest a boundary between two urban classes, marking the invisible divide between north and south Tehran. In contrast, the Tehran Metro (Print 2) carves out an invisible, subterranean zone designed for regulation and control. Yet the metro remains a site of gathering and uprising, where the controlled can become unpredictable and burst into collective expression.

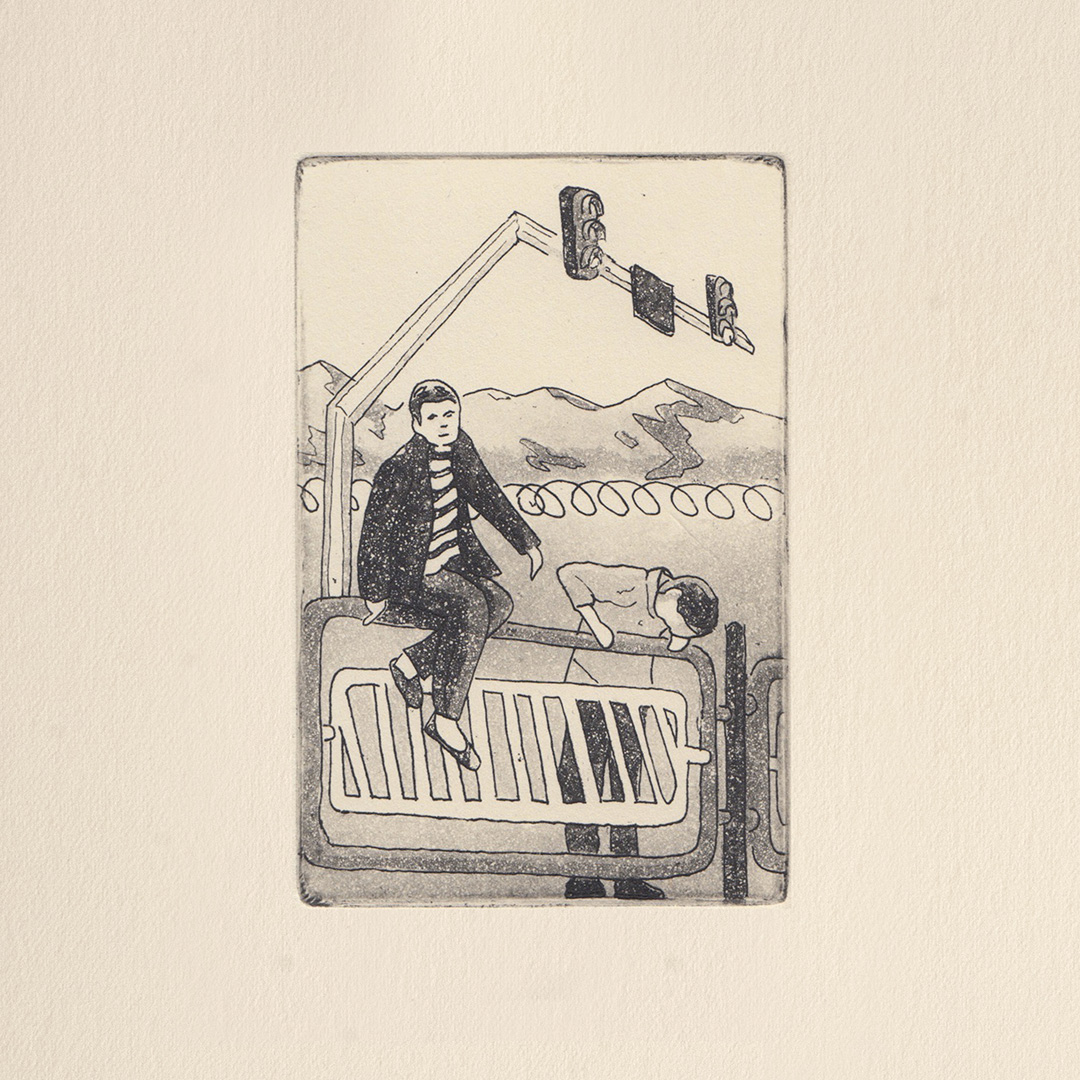

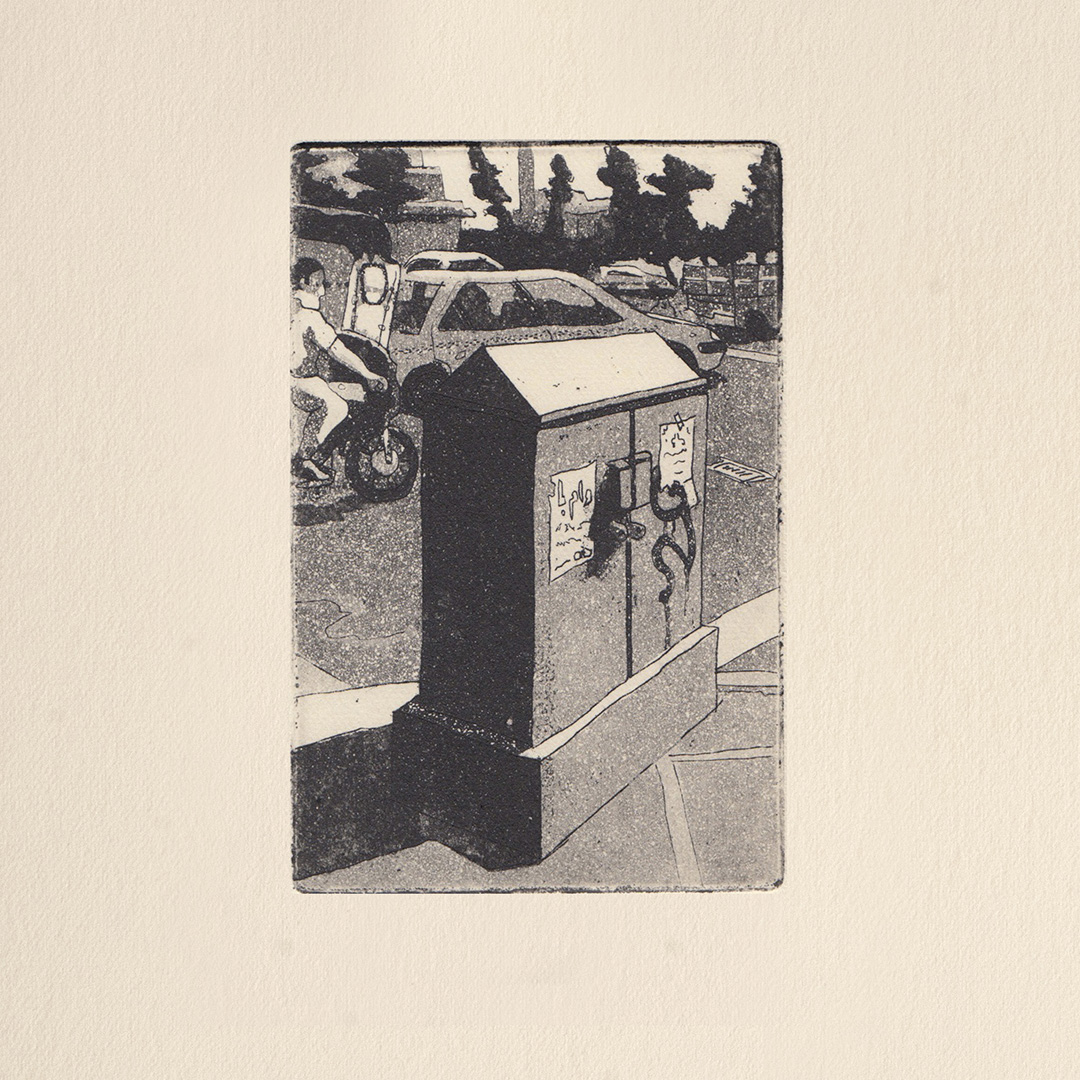

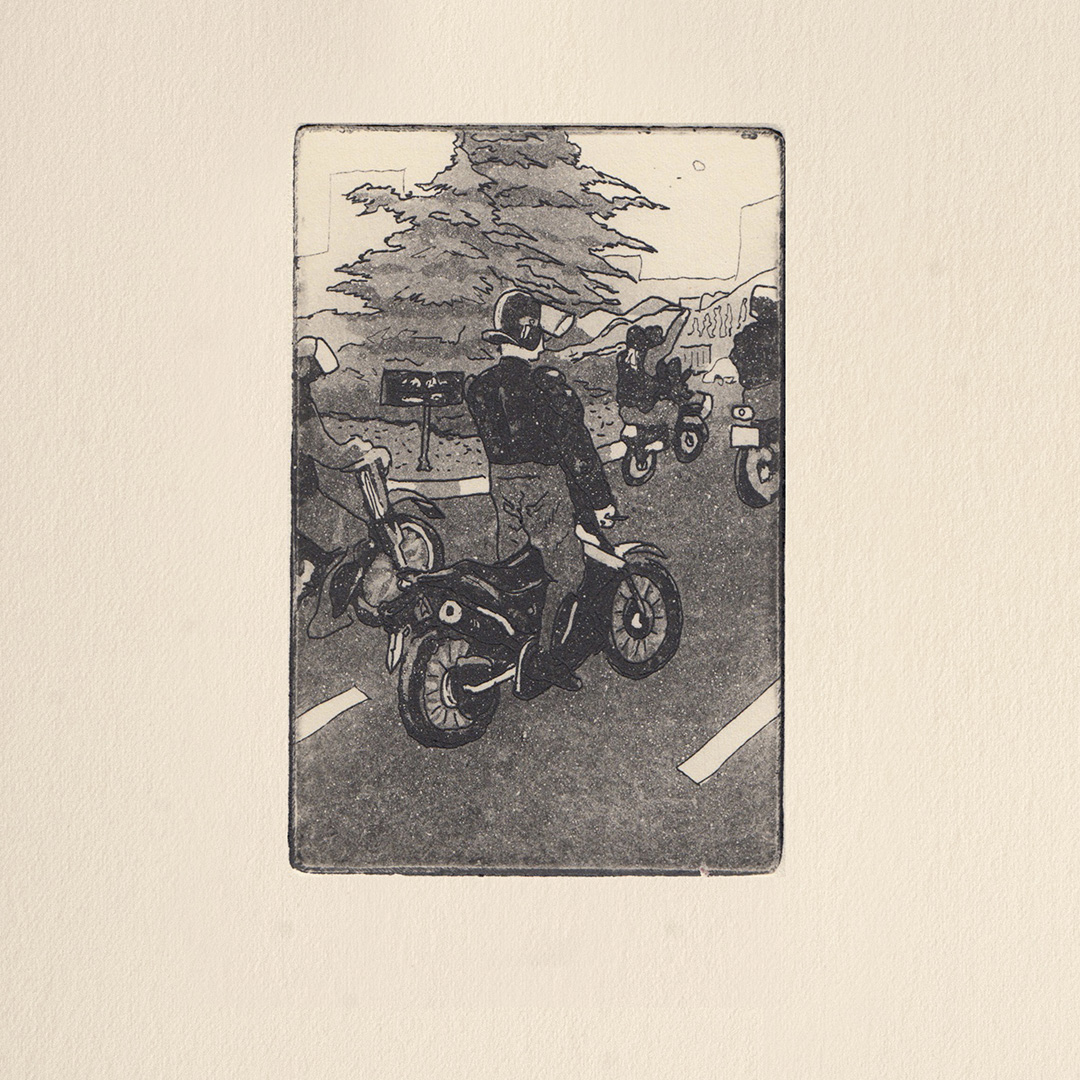

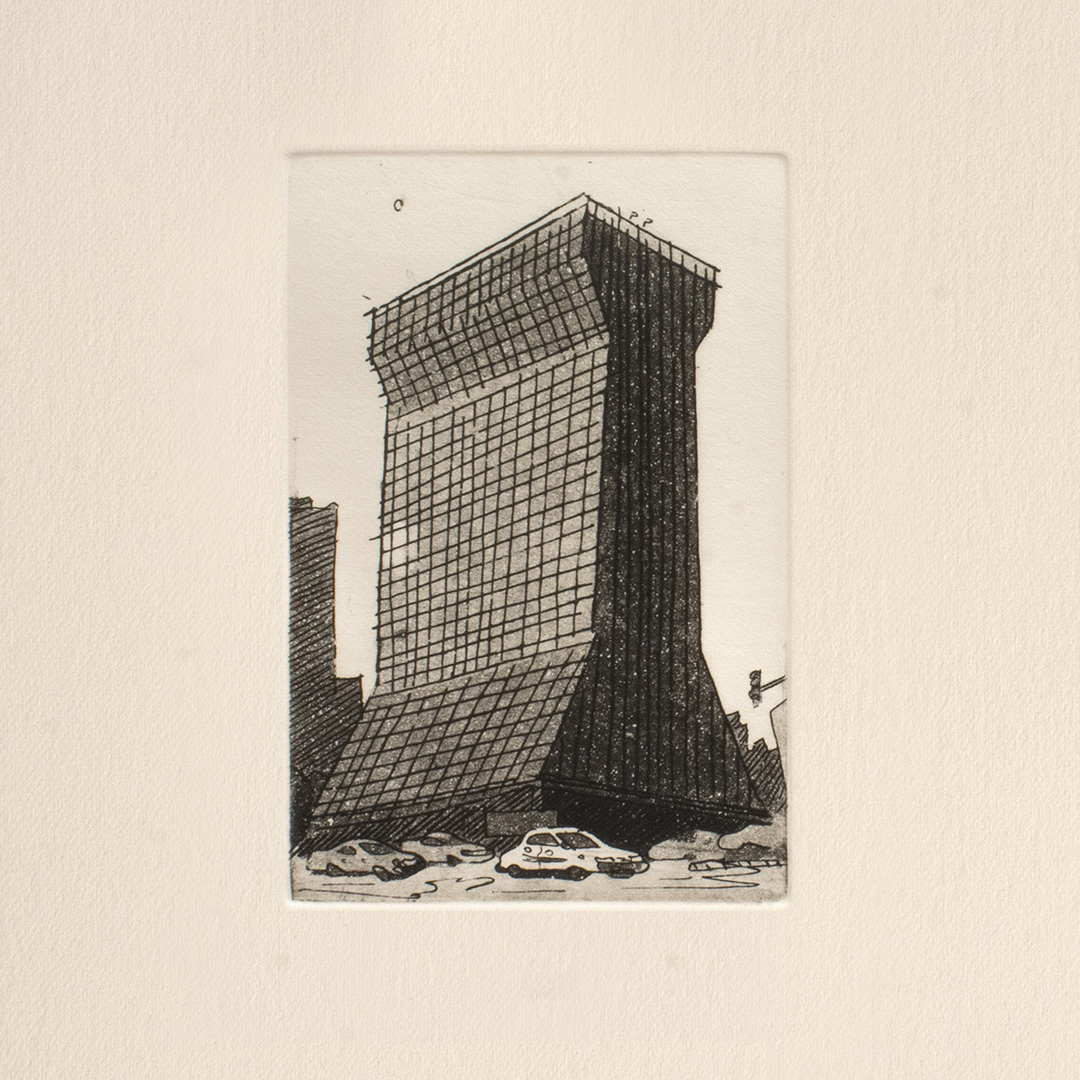

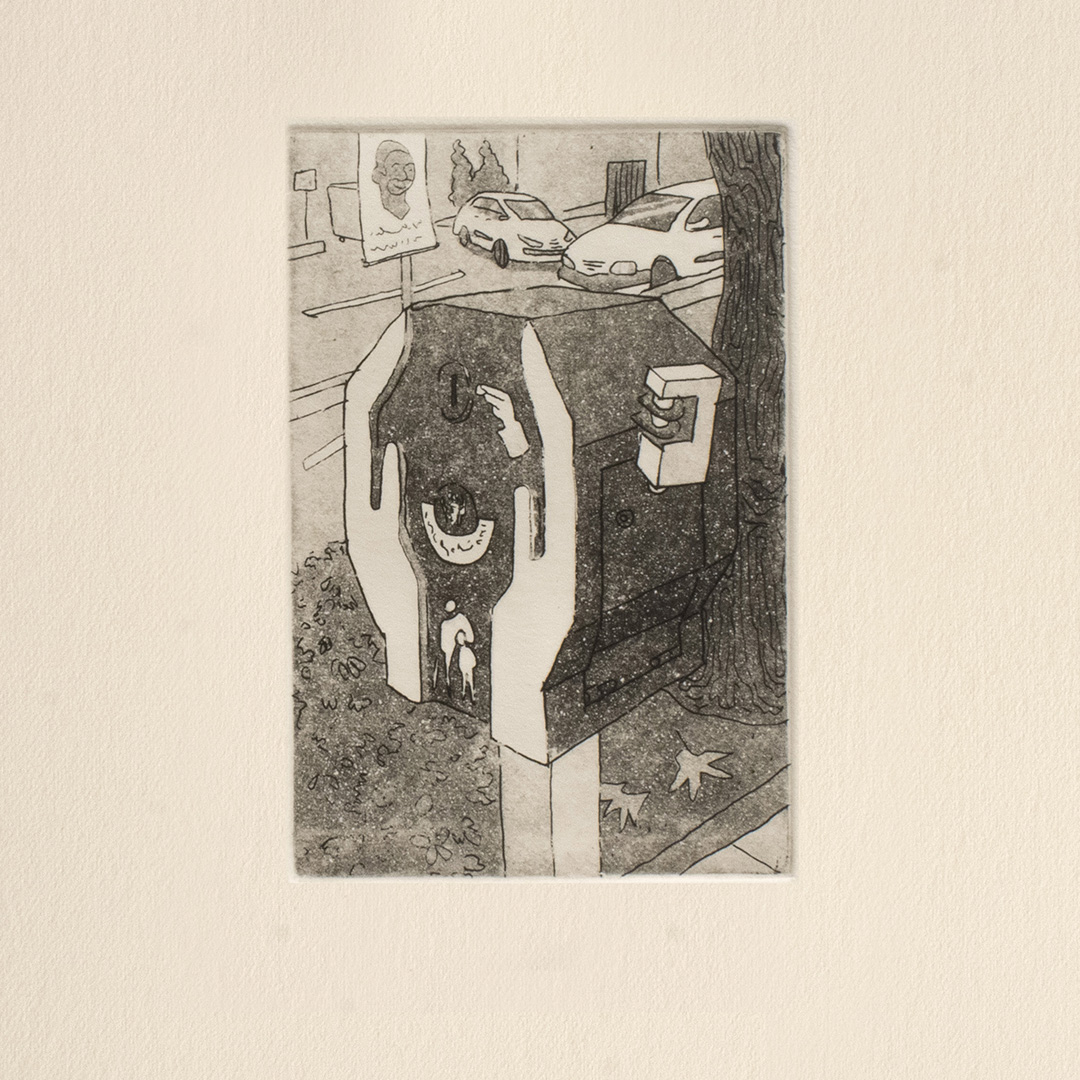

Above ground, the Ministry of Interior (Print 3), built before the Islamic Revolution, and the relief sculpture at Enghelab Square depicting the leader of the revolution (Print 4), speak to the architectural endurance of power, regardless of who governs. But not all sites of control are monumental. A fence on Enghelab Street (Print 5) is climbed by citizens defying urban constraints that divide Tehran socially and physically. In Print 7, the presence of riot police on motorcycles fills a square with a sense of threat, turning everyday space into a site of enforcement. On the other hand, the humble electrical box (Print 6), once the platform for Vida Movahed’s scarf protest, presents a quiet symbol of one of Iran’s most significant freedom movements.

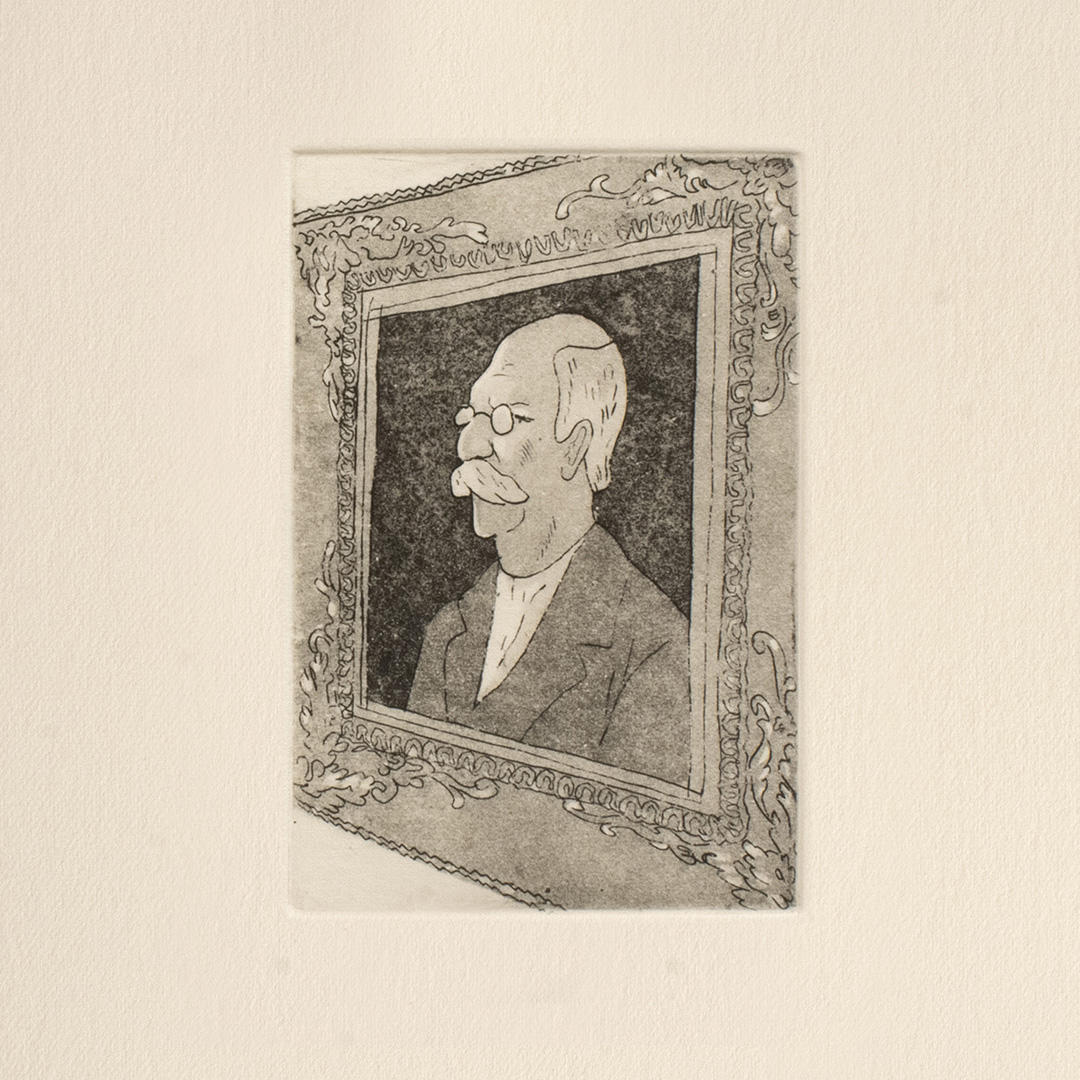

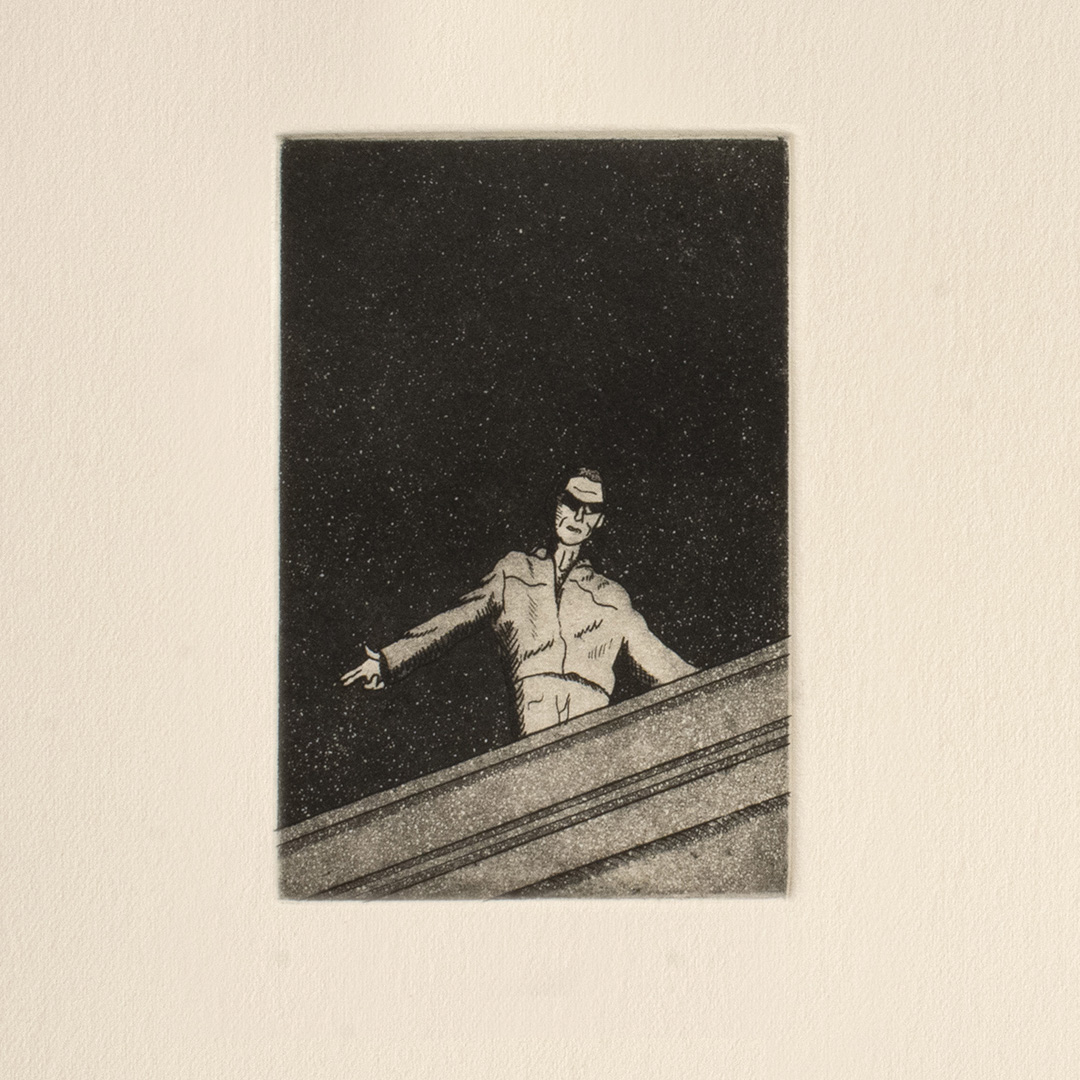

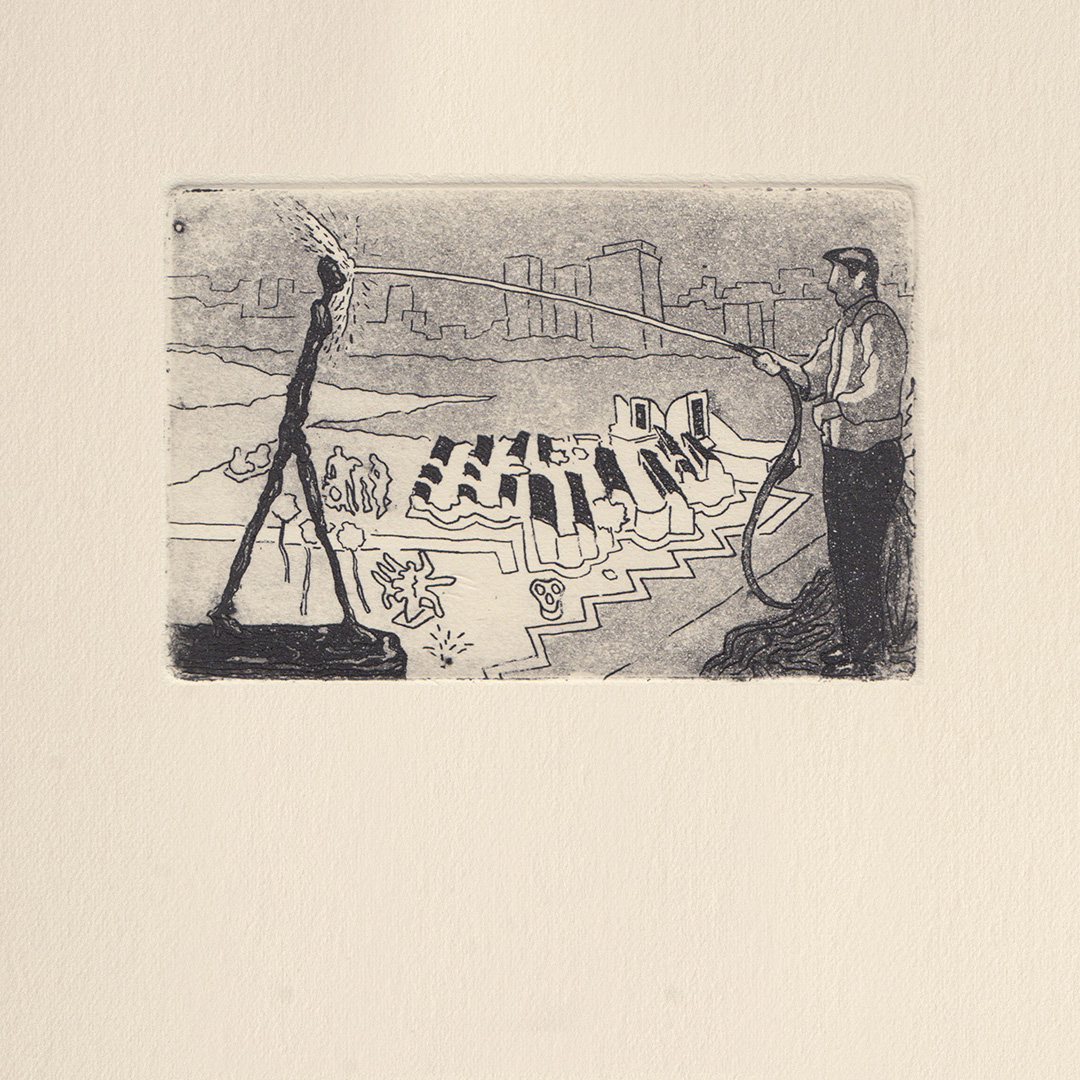

Prints 12 and 13 present two figures who occupy radically different positions within Iran’s cultural spectrum. Kamāl-ol-Molk, court painter to the Qajar and Pahlavi kings, appears framed and idealized in Tehran Museum of Contemporary Arts’ canon. Right beside him, Dorcci, a young underground rapper, is captured mid-performance on a Tehran rooftop, chanting “Fuck it” as a raw mantra. The juxtaposition raises the question: Who defines cultural legitimacy, and who speaks for the present moment? Print 11, a surreal image of a museum worker spraying down a Giacometti sculpture with a garden hose, questions institutional carelessness and the vulnerability of cultural heritage in the hands of those charged with its preservation.

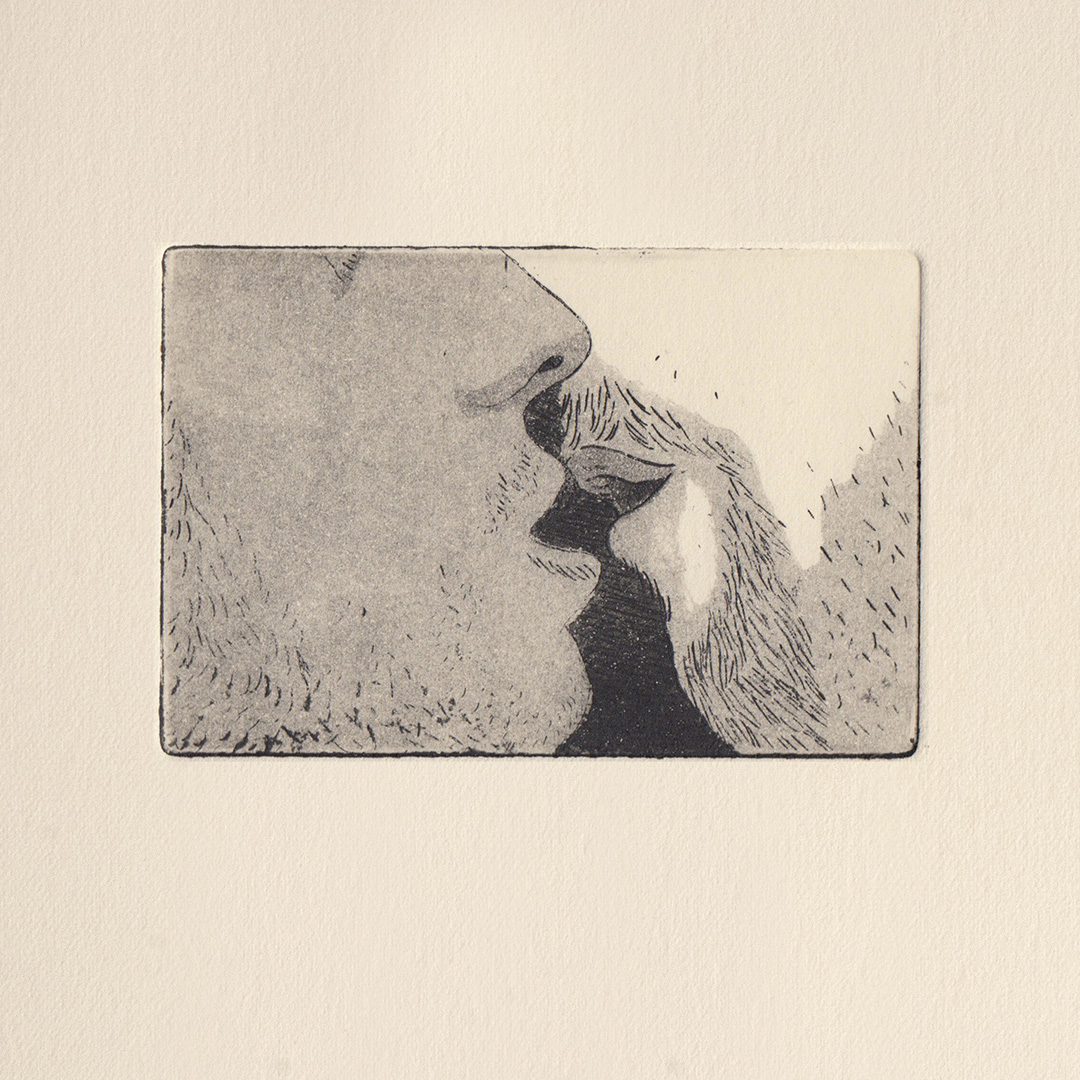

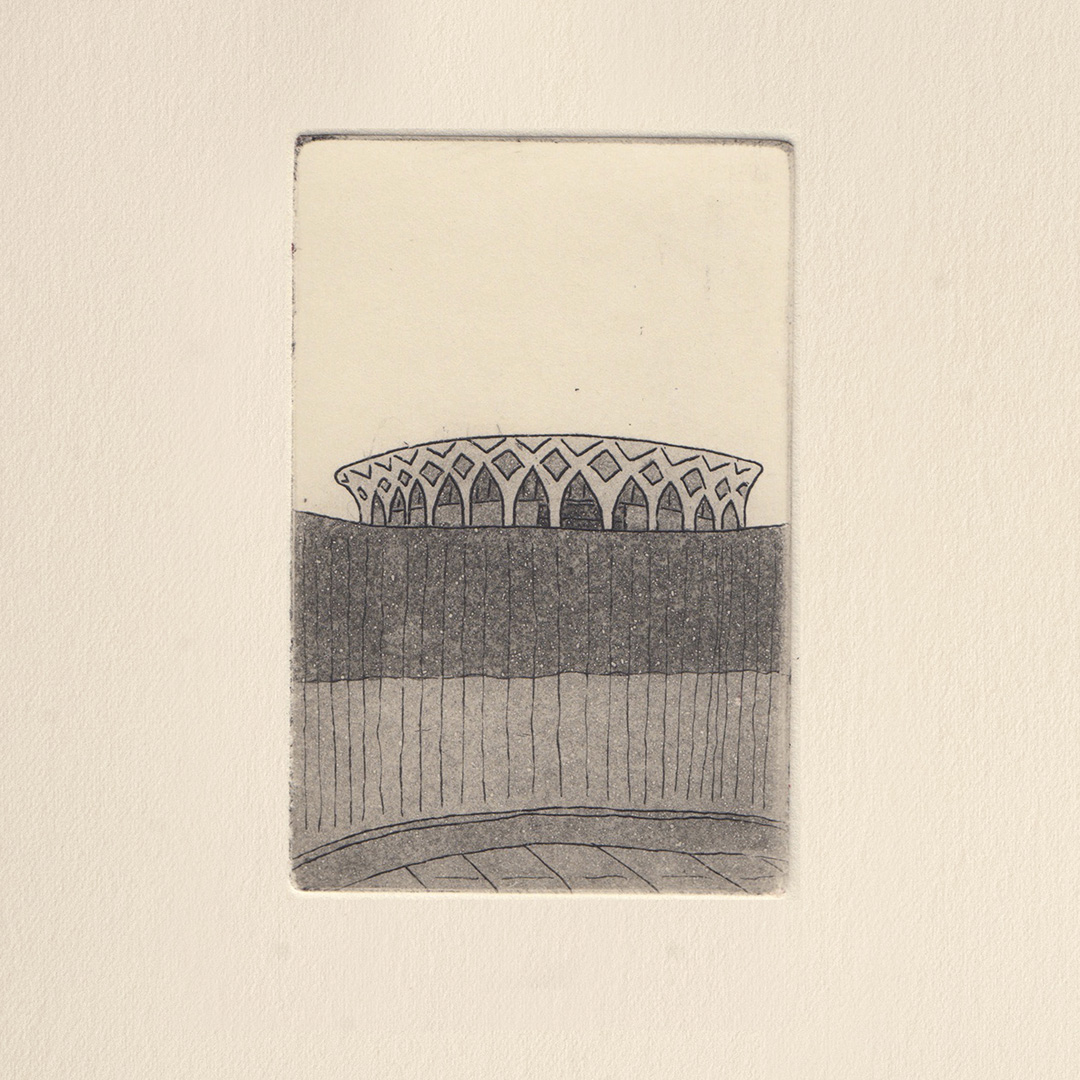

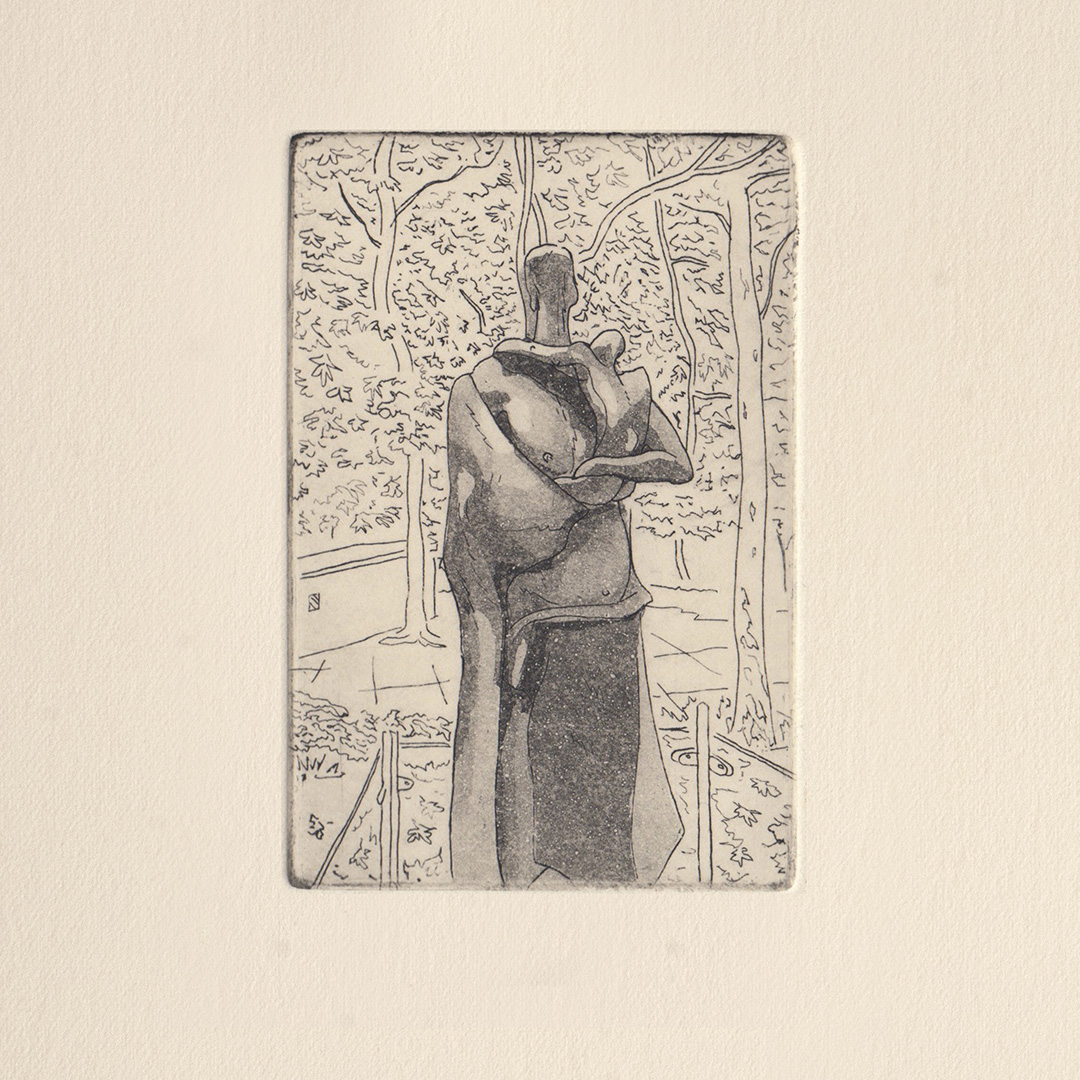

The private embrace of two men in Print 10 offers another view of a reality rarely allowed into public discourse. Intimate and quiet, the scene reflects a life lived outside official recognition. Print 8 shows the City Theater at Valiasr Intersection, once a lively urban commons and a famous meeting point for homosexual and transgender men and women. Its building and public space are now walled off under the pretext of renovation. This restriction echoes a longer process of disappearance, seen in Print 9 with the sculpture Mother and Child by Bahman Mohassess—the prominent gay painter and sculptor, one of the few public nude works to survive the purges after the revolution.

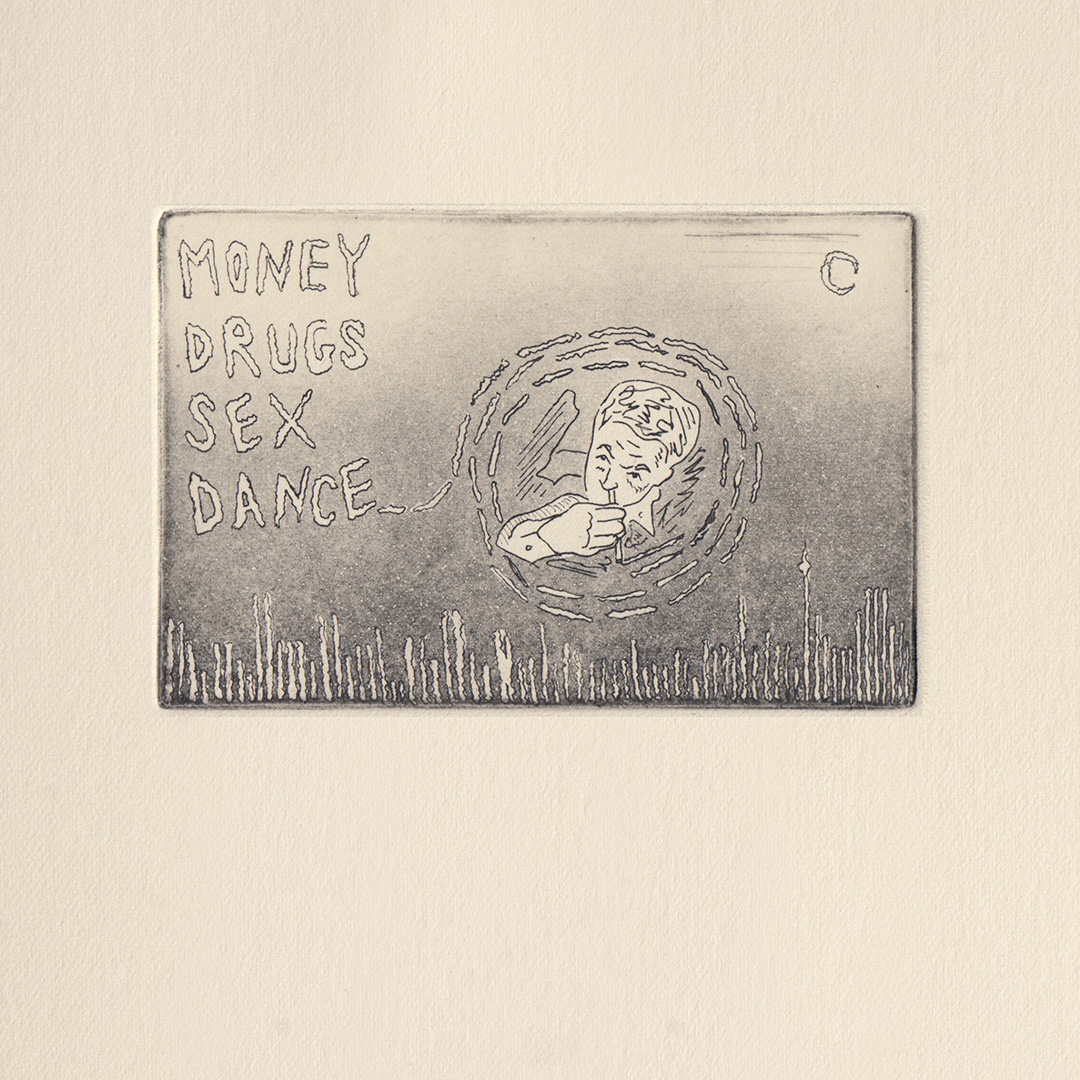

In Print 14, the scene turns toward a different kind of concealment: the underground party. A figure inhales drugs at dawn, surrounded by lyrics, symbols, and cocaine lines that blend into Tehran’s skyline. This is a portrait of hidden freedom, spaces where music, dancing, and self-expression persist in defiance of surveillance. But this defiance comes at a cost. Due to the paid nature of these parties and the high price of drugs, MONEY also gains special importance in these spaces, much like in other aspects of Iranian society.

Prints 15 and 16 explore a tension embedded in Tehran’s urban economy. On one side stands the central Tejarat Bank, a grand edifice designed by Vartan Hovanessian, representing financial authority and institutional wealth. On the other hand, a locked charity box installed on the street pleads for aid to support the city’s poor. The lock, added due to frequent thefts, mirrors the vaults of the banks, suggesting how tightly guarded resources have become. These images speak to a widening social gap, where economic disparity is inscribed into the very infrastructure of daily life, from underground parties to architecture and urban objects.

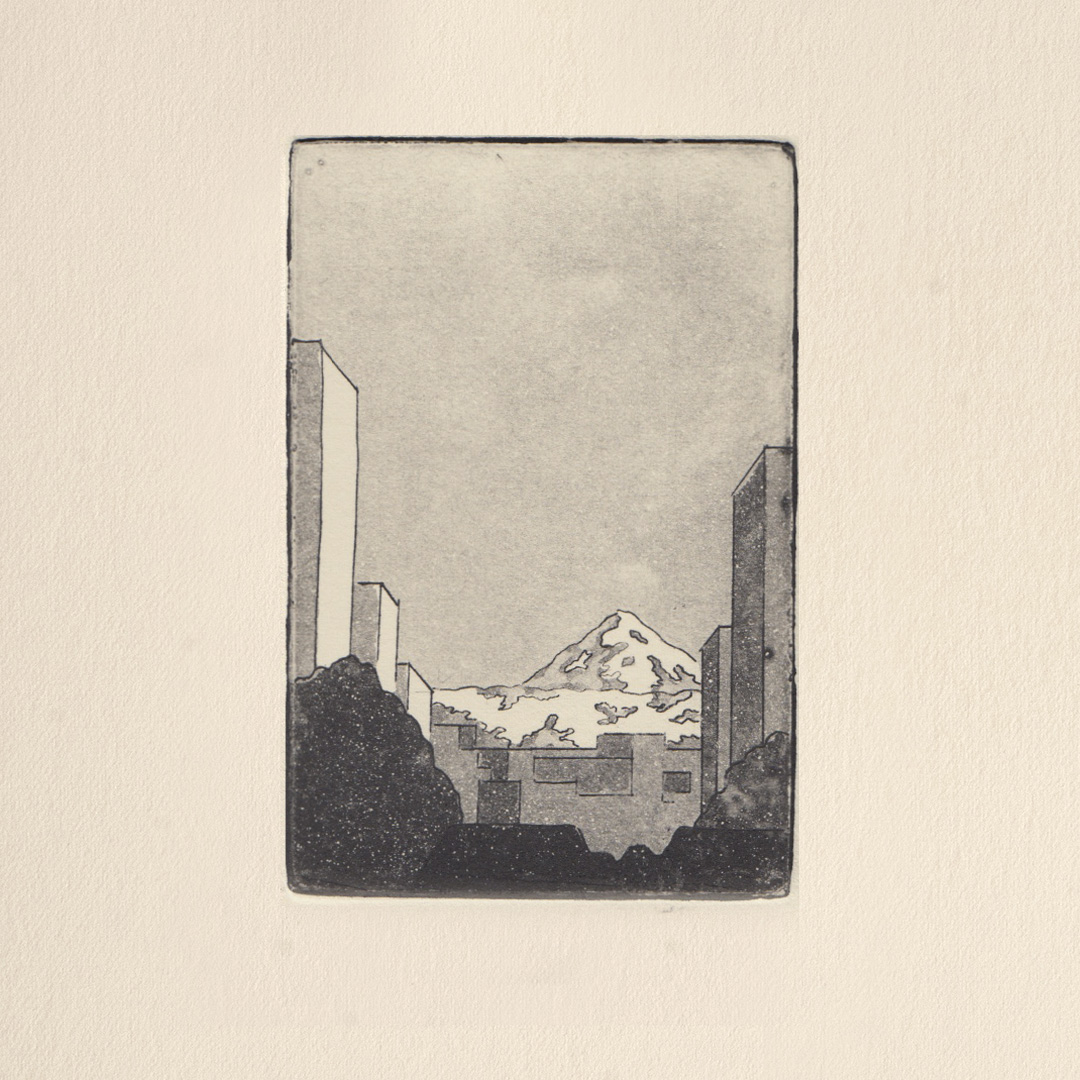

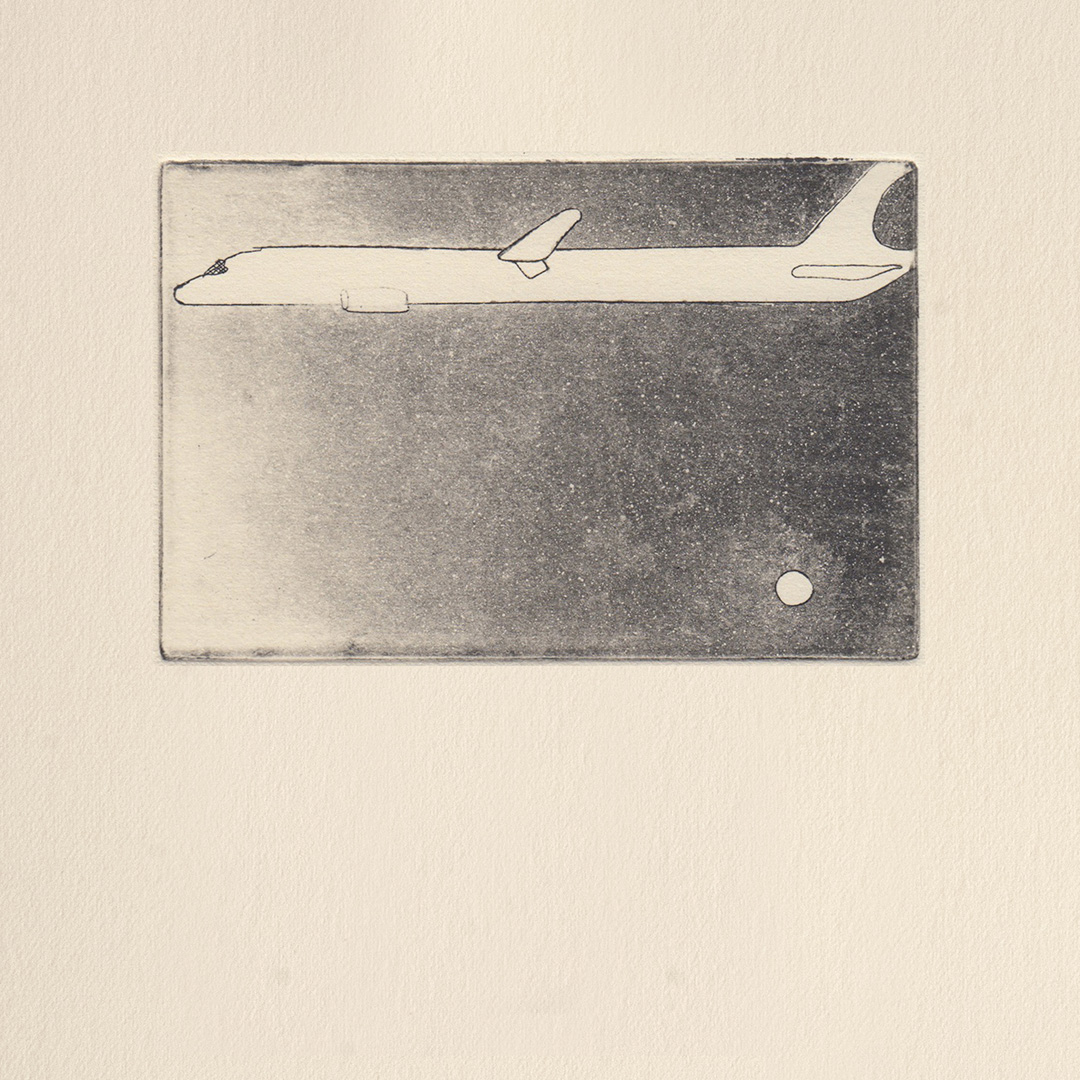

From a mundane object in Print 16, Print 17 shifts the gaze to Mount Damāvand, rising above Fatemi Street, a natural landmark that endures beyond political regimes and the fluctuations of the city. As Iran’s highest mountain and a storied symbol in Persian myth, it represents resilience, spiritual ascent, and the promise of horizons beyond the city’s concrete cage. Print 18 returns us to the desire for escape: a lone airplane disappears into a glowing sky westward, evoking both the longing for freedom and the heartbreak of migration. These two prints reflect the city’s outer limits, one ancient and grounding, the other propelled by the need to flee.

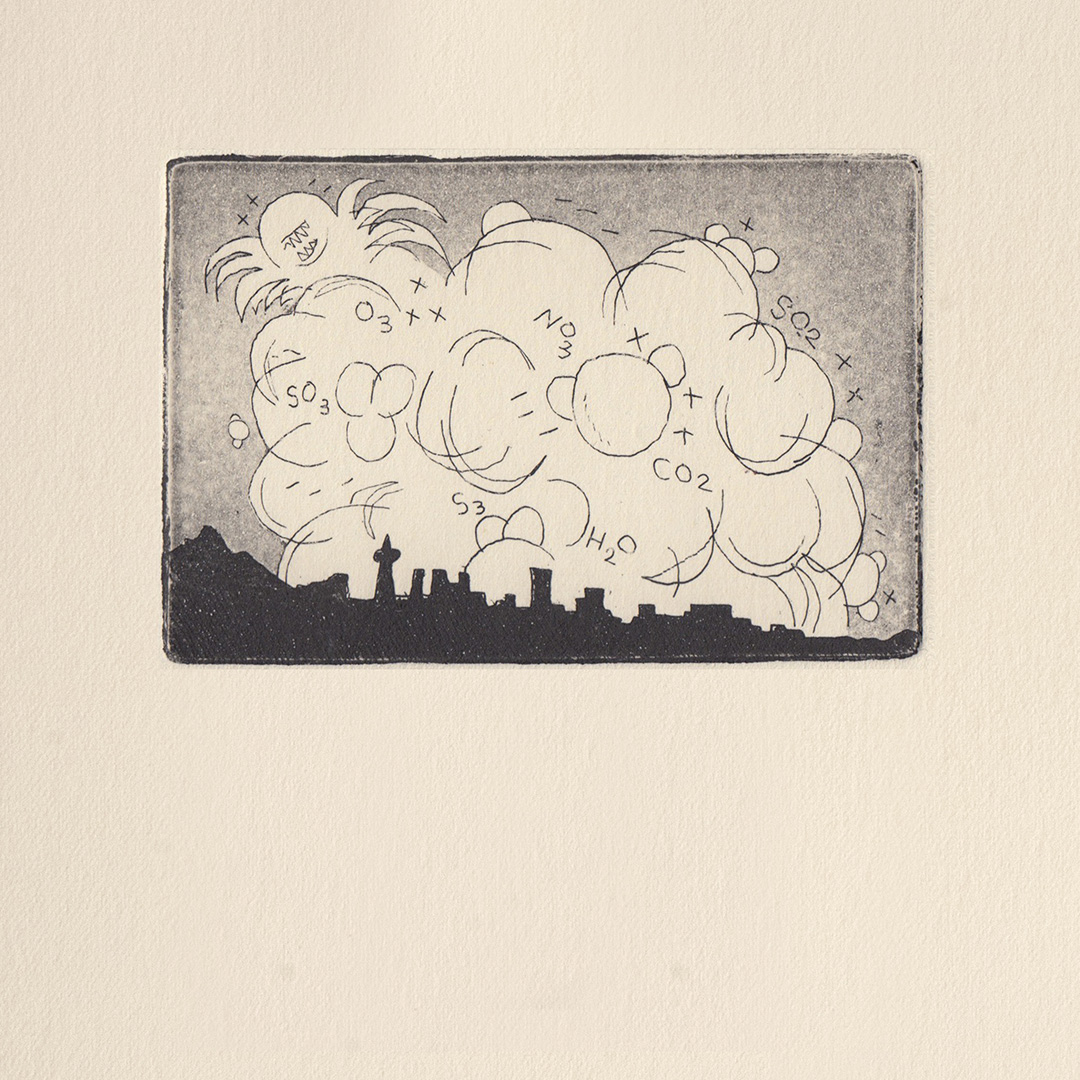

The final print shows Tehran beneath a poisoned sky. The city dissolves under chemical formulas and a grinning emoji, capturing a surreal kind of suffocation. Here, the issue is neither political nor cultural, but environmental. Pollution, ecological threats, and the shadow of war become the city’s silent governors, unrelenting and unaccountable.

These etchings do not attempt to present Tehran as unified or easily understood. Instead, they offer fragments, each image a moment suspended between the past and the unfolding present. Through overlooked corners, improvised actions, and persistent figures, this collection invites viewers to examine how Tehran shapes its people, and how people, in turn, attempt to reimagine their city.